When you started your climbing career, you probably questioned whether or not rock climbing was dangerous.

Of course, it’s not at all a silly question, as purposefully hanging by your fingertips from the top of a 100m (300ft) cliff doesn’t exactly sound like the kind of thing we should do if we want to minimise risk in our lives.

The short answer is yes, climbing is dangerous, but so are a lot of things that we actually consider to be safe. Perhaps a better question to ask is what are the consequences of something going wrong and what is the risk of that outcome occurring.

At the end of the day, we humans have a somewhat odd perception of what is “dangerous” and what isn’t in our daily lives.

We tend to focus our fears of danger on “extreme” activities such as rock climbing, heli-skiing, and mountain biking when, perhaps, these fears would be better placed in more “day-to-day” activities, such as driving a car, eating excessive amounts of junk food, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

As you might imagine, however, any discussion of whether or not climbing is dangerous is a difficult one, indeed.

While the general non-climbing public thinks that climbing is one of the most dangerous things you can do, climbers seem to not only accept this danger but embrace it and take it in stride.

Thus, we’ve decided to settle, once and for all, the question, “Is rock climbing dangerous?”

To answer the question, we’re going to discuss the meanings behind the words “safe” and “dangerous” and talk about different ways we can manage risk in the climbing environment.

Here we go!

What is “safe,” anyway?

These days, many people are very “safety” conscious.

Through modern technology, laws, policies, and administrative oversight, we’ve worked hard to eliminate unnecessary dangers from our lives, whether that be through eradicating diseases or enforcing speed limits on motorways.

While avoiding needless and accidental death is, of course, a good thing, these risk-adverse practices have helped create a population that thinks that adding a speed limit to road makes it “safe,” when, at the end of the day, a drunk driver could easily be going the speed limit, but cross over to the other side of the road and cause a 10 car pile-up.

The problem here is not the speed limits, the regulations in effect, or the cars themselves. The problem is that we live in a world where the vast majority of people believe that something can be “safe.”

So, what does “safe” mean?

Technically, “safe” means “without risk.” There is not a single thing in this world that you can consider to be “safe” as everything has risk.

A “safe” wisdom tooth removal surgery can easily go south if the patient has an adverse reaction to anaesthesia.

A “safe” water supply can have dangerously high levels of lead in it if no one is paying proper attention to testing (see: Flint, Michigan, USA).

Thus, many of the things we take for granted as being “safe” in the Western world are not at all “safe.”

Instead, they are just low risk.

Therefore, when we think of things in terms of a safe/dangerous binary, we will always end up in a pickle.

Instead, we need to look at the relationship between hazard, risk, and consequence, in any given situation.

Hazard, Risk, and Consequence

The terms hazard, risk, and consequence are often incorrectly used interchangeably to mean the same thing.

However, they have very distinct definitions that are important to understand, especially if you spend a lot of time in dynamic environments, such as the outdoors.

To start things off, let’s define each of these terms:

Hazard

A hazard is anything that has a negative consequence (more on what that is in a minute).

Hazards are inherently dangerous, which means they can cause injury, whether that be physically, mentally, emotionally, financially, or otherwise.

Hazards can be either objective or subjective, depending on what causes them.

Objective Hazards

An objective hazard is one that exists whether or not a person plays a role in their occurrence.

This includes naturally triggered avalanches, naturally triggered rock fall, lightning, and other such events.

While there are things we can do to lessen our exposure to these hazards, a tree can fall whether or not someone was there to see it happen.

Subjective Hazards

A subjective hazard, on the other hand, is one that exists at least partially because of some human action.

This includes events such as a negative bear encounter, getting swept away by a big river crossing, or falling from a climb.

These hazards can only happen when we humans are involved; a bear can’t have a negative encounter with a human unless a human is near the bear.

Risk

Risk is the likelihood of a hazard occurring.

What’s important to note here is that the risk of something happening (i.e. the likelihood of it happening) is always changing.

Risk of an event changes based on factors such as the skill level of a person or a group, the environment that person or group is in, or the current weather conditions.

Ultimately, risk is just the likelihood or probability of a hazard actually happening to you or your group at a given time.

But, what’s important to understand is that we cannot ever truly eliminate risk – we can only minimise our likelihood exposure to risk to the best of our abilities.

Consequence

Consequence is what can happen if a hazard occurs.

For example, if a group has a negative bear encounter and the bear decides to attack the group, they can get away with minor injuries or they can face death.

Consequence has nothing to do with the risk of an event; rather, the consequence of a hazard should give us insight into how much and what kinds of risk management tactics we should employ or make us consider whether or not we actually want to assume these risks.

What all this talk of hazard, risk, and consequence actually means

The problem with the terms, hazard, risk, and consequence, as we’ve previously mentioned, is that people often conflate them and attempt to use them interchangeably.

Thus, to give you an idea of how you can use these terms correctly here’s are two examples:

Scenario A

When Alex Honnold, the world-famous climber, goes out to free solo (climb without a rope) the 1000m (3000ft) El Capitan, he is exposed to the subjective hazard of a ground fall.

The risk of this fall for Alex, is actually quite low, as Alex Honnold is a very skilled climber.

However, the consequence of such a fall is death.

Scenario B

If I, Gaby Pilson, a not-at-all famous climber, go out to free solo El Capitan, I am exposed to the subjective hazard of a ground fall.

The risk of this fall is quite high as I am not nearly strong enough or skilled enough to take on such a climb, to say nothing of the mental fortitude required to climb 1000m without a rope.

The consequence of such a fall is death.

What was the difference between these two scenarios?

The only thing that changed in these scenarios was the climber and their skill level.

What this means, however, is that both climbers face the exact same hazards and the exact same consequences, but face entirely different levels of risk.

Alex Honnold is actually exposing himself to much less risk than Gaby Pilson is in this scenario, despite the fact the consequence that both climbers face is death by ground fall.

Thus, what we should be talking about when we talk about danger, is neither the risk nor the consequence of an activity such as climbing, but rather, the relationship between risk and consequence in that activity.

Risk v. Consequence

When we make a decision about whether or not we should or should not do an activity, we need to weigh the consequences of that activity with the risk – or likelihood – of that consequence actually occurring.

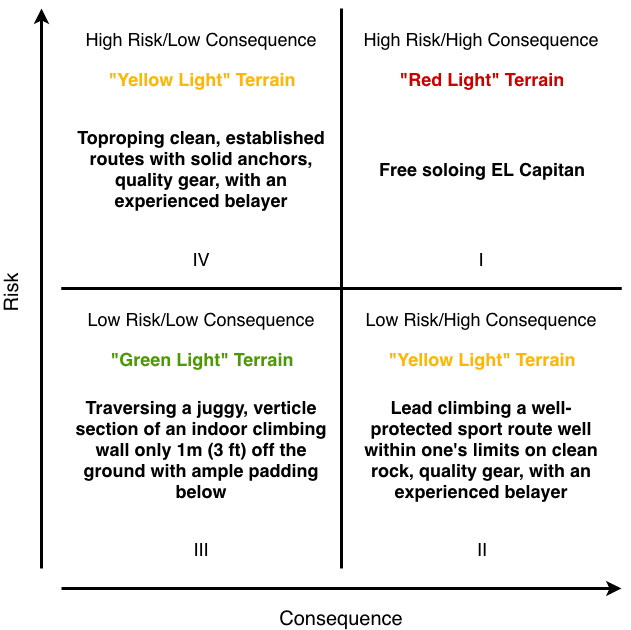

To help us balance risk and consequence in our decision making, we can use the Risk v. Consequence model.

This model, as pictured below, uses a graph to help us visualise the different types of situations we might encounter in the outdoors.

If we plot consequence on the X-axis and Risk on the Y-axis, we are left with four quadrants, each representing a different intersection between risk and consequence.

In quadrant I, we have high risk/high consequence activities, such as travelling through an active rockfall zone.

We would consider this “red light” terrain, which means it’s best avoided as it’s difficult, if not impossible for most of us to mitigate the risk of these activities to an acceptable level.

In quadrant II, we have low risk/ high consequence events, such as a bear attack.

While the many people think that bears pop out of nowhere and attack humans on a whim, the fact of the matter is that bear attacks are quite rare, and often only happen when we store food improperly or interfere with a bear.

Thus, while a bear attack is a pretty high consequence, there’s actually a fairly low risk of it happening. We dub this “yellow light” terrain because there are things we can do to keep our risk of a bear attack low, such as carrying bear spray or travelling in a group.

In quadrant III we have low risk/low consequence events, such as stumbling on a flat trail.

For most people, stumbling on a flat trail is unlikely, but even if it does happen, it’s not likely to cause any serious injury. Usually, the worst thing that happens is that the hiker walks away with a bruise and a scratch but is ultimately okay.

This is what we’d call “green light” terrain. While this doesn’t mean we can completely forget about risk management here, it does mean that something really bad is fairly unlikely to happen.

Finally, in quadrant IV, we have a high risk/low consequence events, like a sunburn.

Although we all know that we should put on sunscreen and cover our skin in the sun, we often neglect to do so.

Thus, sunburns are fairly common events, though, thankfully, their fairly low consequence, at least in the short term.

Similar to quadrant II, quadrant IV is “yellow light” terrain, because there’s a lot we can do to minimise our risk of sunburns, such as frequently applying sunscreen when we’re outside.

How do we use this information to understand climbing?

Ultimately, this model is designed to help us think about the hazards we subject ourselves to in a more logical manner.

While the “human factor” – that is, the traps we fall into when we’re motivated more by summits or other desires than to stay alive – certainly has an effect on our decision making, the point of such a model is to put logic in the foreground and other motives far in the background.

Thus, for many of us, we need to decide what falls within our “yellow” and “green light” terrain and what’s a no-go activity within our “red light” terrain. For many climbers, this would probably look something like this:

Once we get to this point, however, we need to determine how we are going to mitigate the risks we face in yellow light terrain.

If we consider the different types of climbing that most climbers enjoy, we see that we already have a significant number of risk management practices in place. Whether or not a climber chooses to follow these accepted practices, is another story.

Let’s, for argument’s sake, consider free soloing to be the “purest” form of climbing.

It’s just the climber, the rock, the vertical world, and the power of gravity. No ropes, harness, or carabiners to get in the way.

For the vast majority of us, free soloing is high risk/high consequence “red light” terrain.

Thus, we mitigate the risk of free soloing by adding in harnesses, dynamic nylon ropes, fancy carabiners, slings, cams, nuts, the whole nine yards.

By doing so, we move “pure” climbing into “yellow light” terrain.

For example, if a climber decides to go lead climbing on a well-protected sport route that’s well within their limits, on clean rock, quality gear, and with an experienced belayer, they have moved climbing into terrain that’s not terribly likely, but if something did go catastrophically wrong (think: total bolt failure and ground fall), the consequences are quite severe.

At the same time, a climber who chooses to go toproping on clean, established routes with solid anchors, quality gear, and an experienced belayer is likely to take a toprope fall (especially if the route pushes their physical limits) but any well set-up toprope should expose a climber to a very small, low consequence fall.

Additionally, someone who chooses just to traverse the bottom 1m (3ft) of a juggy, vertical section of an indoor climbing wall that has ample padding underneath, faces a fairly low risk of falling and a fairly low consequence if they do (probably a sprained ankle, at worst).

Thus, people who follow the standards for generally acceptable practice in climbing, seek out qualified instruction, follow gear manufacturer’s recommendations, and know their personal limits are doing well to mitigate risk in their climbing lives.

Sure, anything could happen – a huge earthquake could cause massive rock fall, a critical hold can break under your foot in an exposed section, you could faint in the middle of a climb, but all of these things are part of the game we play as climbers.

All of these things are part of the game we play called life. We are constantly exposed to hazards, both in climbing and in life.

Any belief that we can eliminate all risk and do away with all hazards in either climbing or our day to day lives is misguided at best and dangerous, at worst.

So, is climbing dangerous?

Ultimately, the answer to the question of “Is climbing dangerous?” is a simple one – yes, it is.

Climbing is, indeed, dangerous, because we can’t consider it to be “safe.” But, at the same time, nothing we do is actually “safe.”

All we can do is manage risk to the best of our abilities and make good decisions in tough circumstances.

The vast majority of climbers want to make it home at the end of a climbing day.

Climbers, for the most part, are a responsible bunch, even if they do have a propensity for high places. Responsible climbers seek out qualified instruction to learn the proper skills and techniques they need to manage risk and get themselves out of a difficult situation.

They don’t blindly follow the direction and leadership of others and they practice active followership when they don’t feel comfortable in a situation.

Responsible climbers understand the tenuous relationship between hazard, risk, and consequence, and they take the time to stop, look around, and assess a situation before diving head first into unknown waters.

All of this happens in the same way that a responsible driver wears their seatbelt, drives the speed limit, and looks behind them before pulling out of a parking spot.

So, yes, climbing is dangerous. But what isn’t?