A modern-day climber is as likely to find themselves inside pulling on plastic as they are to be climbing some classic multi-pitch routes in Red Rock. While cragging and indoor climbing may be the name of the game for contemporary climbers, those who led the way as climbing trailblazers in the sports early years could never have anticipated how climbing would develop from its humble beginnings.

The history of climbing is a long one and any good discussion of it will certainly be a marathon, not a sprint. So, pull up a chair and grab a cup o' coffee as we dive right into the long and storied history of climbing.

Early Beginnings

People around the world have been climbing to high places for food, resources, and the like since time immemorial. While villages and settlements at high elevations exist in countless locations and people have been trudging their way to the tops of mountains and hills out of necessity for generations, technical climbing as we know it is a relatively modern phenomenon.

The first documented rock climber, however, did not climb for fun or fame, but rather to fulfil a royal command. In 1492, Antoine de Ville ascended Mont Inaccessible, a 300-meter tall rocky tower on Mont Aiguille near Grenoble, France on orders from King Charles VIII of France. Using techniques originally developed for the sieging of castles during wartime, de Ville used ladders and ropes to make it to Inaccessible’s summit, where they stayed for six days and erected three crosses to prove their ascent, which would not be repeated until 1834.

Although such an ascent may seem minor today, de Ville’s climb is important within the history of climbing both as a physical feat and a paradigm of the contemporary discourse surrounding mountains and wild places.

Romanticism, religion, and the sublime in the mountains

When Edmund Burke first connected the concept of the sublime with an experience of awe and terror in his 1757 treatise, Philosophical Enquiry, he did so in relation to the thrill and the danger of confronting Nature in its untamed and wild form. One could find such a romanticised wilderness in a deep chasm, a thunderstorm, or at the foot of a jagged alpine peak.

The awe and reverence that Burke and other Romantics felt for the wild were not secular beliefs, however, as the sublime, they argued, demonstrated the immense power of God in the human world. Thus, what is most interesting about de Ville’s 1492 climb of Mont Inaccessible, is not the ascent itself, but the establishment of three crosses on the tower’s highest point.

The connection between the Romantics’ view of the sublime and Christian ideals is not an accidental one. As we have seen, God is omnipresent in the very concept of the Romantic’s sublime as both a source of awe and omnipotence. This notion of a god-filled sublime, while first written by the Romantics, is not, however, new.

Rather, the connection between feelings of terror and the unknown have been linked with Christian concepts of wilderness since their inception. Indeed, throughout both the Old and New Testaments, natural and untamed places are consistently connected with sentiments of fear.

Thus, the very notion that anyone would willingly head into the mountains and use physical strength to climb to the top of a sharp, jagged peak would have been ridiculous to the Romantics and the people who came before them. The concept of climbing a mountain or, better yet - a cliff - for fun, would’ve been absolutely ludicrous.

So how did we get from a terror, awe, and fear in the face of mountains in the 1700s to the modern-day invasion of climbing into popular culture? How did we transition from Burke’s treatise on the sublime to #themountainsarecalling and the veritable swarms of Instagram-inspired visitors to our wild places? What changed and how did it happen?

Mont Blanc: The beginning of an era

As the tallest mountain in the European Alps, Mont Blanc has long held a special place in the hearts of adventurers and mountain enthusiasts around the world. Tall and jagged, with steep, foreboding rock faces hanging high above the Valley of Chamonix below, Mont Blanc is certainly a sight to behold - and a true experience to climb.

Despite - or perhaps because of - Burke’s infatuation with the raw power of the natural world and the sublime, some of the wealthy aristocrats of 18th century Britain started setting off on holidays to the Alps to enjoy the fresh, mountain air. Some of these aristocrats quickly found that hanging out at chalets on the valley floor just wasn’t exciting enough and started to search for something new to whet their appetite.

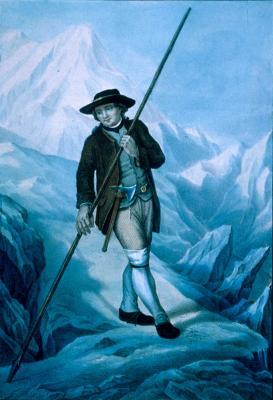

One of these aristocrats, Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, was so infatuated by the Alps and their unique geology and botany, that he wanted to set out on an adventure and climb the stunning Mont Blanc. Despite his best efforts, however, de Saussure was unable to climb Mont Blanc on his own, so he offered a public reward in 1760 to anyone who could help him get to the top.

De Saussure’s prize money went unclaimed for more than 25 years until a 26-year-old crystal hunter named Jacques Balmat came onto the scene. Balmat was hired by a Chamonix doctor - Michel-Gabriel Paccard - as a porter as he attempted to reach the roof of Europe. Despite his position as a porter, Balmat was essential to the duo’s eventual success and summit of the peak in 1786, which was done unroped and without ice axes.

After his first summit of the mountain, Balmat then helped de Saussure climb to the top of Mont Blanc just one year later. For these feats, King Victor Amadeus III gave Balmat the honorary title, du Mont Blanc. Although his achievement often goes unrecognized in today’s climbing world, Balmat’s 1786 climb of Mont Blanc truly set the stage for the golden age of mountaineering that followed.

The golden age

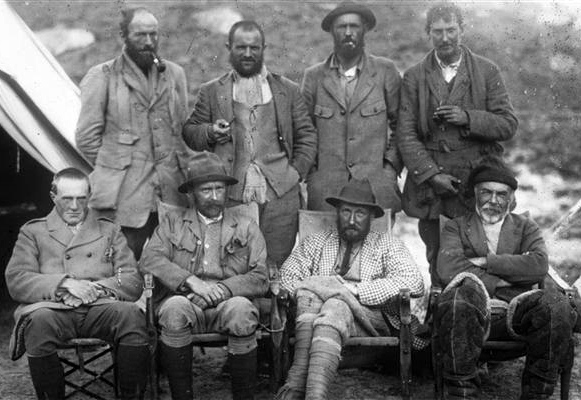

Balmat’s climb of Mont Blanc was, perhaps the first in what would soon become a rich tradition of climbing in the Alps. Although the first climbing club - The Alpine Climbing Club - wouldn’t be founded until about 90 years later, in 1857, the sport was already attracting a following among the well-to-do of Europe.

These climbing clubs were just like any other social club of the era, but instead of just sitting around, playing cards, smoking cigars, and drinking port, climbing club members liked to head out into the hills and test their strength against some of the test pieces of the day alongside their talented, and often overshadowed, local climbing guides. For many climbers, the jewel in the crown of as-of-yet-unclimbed peaks was none other than the Matterhorn - the highest peak in Switzerland.

Known around the world for its dramatic rock faces and sheer cliffs that shoot far up into the sky, the Matterhorn is a truly committing climb, no matter how you set out to accomplish it. Although many had tried to summit the Matterhorn, none had succeeded until Edward Whymper, a young English artist, and his four climbing partners - Lord Francis Douglas, Charles Hudson, Douglas Hadow, Michel Croz, and two Swiss guides - Peter Taugwalder and his son of the same name.

Whymper had actually made eight unsuccessful attempts on the mountain before his fateful climb in July of 1865 finally succeeded in getting to the top. Having ascended, what is now known as the Hörnli Ridge (the current “normal” route up the mountain), the party of seven reached the summit of the Matterhorn at just after 1:40 pm on July 14th, hanging around for about an hour to experience the pure joy of having the world at one’s feet.

The most famous aspect of this climb, however, was not the ascent, but the descent. After they had their fill of the summit, the group began the trek downhill in a rope team. Hadow, just an hour’s hike from the summit slipped suddenly and fell on top of Croz. Both Hadow and Croz continued sliding, pulling Hudson and Douglas down with them. Whymper and the Taugwalders managed to hold firmly onto the rock as the rope broke and their four companions slid out of control and disappeared over a steep edge.

Whymper and the Taugwalders did, indeed, make it back down to Zermatt after their search for their climbing partners ended in vain. Upon their return to the valley, they were hailed as heroes for their first ascent of the last great Alpine peak of Europe, but controversy and gossip naturally ensued in the aftermath of their accident. In fact, Queen Victoria even considered banning climbing for all British citizens, but after some consultation decided not to make mountaineering illegal.

Out of all this joy and sadness, the last great Alpine peak of Europe had, indeed, been climbed. This ascent officially ended what would later be known as the golden age of alpinism, wherein many of the Alps’ most prominent peaks saw their first ascent. This period, which began with Alfred Willis’ ascent of the Wetterhorn in 1854, lasted only a bit over a decade until Whymper’s fateful climb of the Matterhorn in 1865.

After the first ascent of the Matterhorn and the climbing of all of the great alpine peaks of the Alps, many less dominant, but still worthwhile peaks of the Alps saw their first ascents during the lesser-known “silver age of alpinism” between 1865 and W.W. Graham’s ascent of the Dent du Geant in 1882, considered by many to be the last major “prize” of the region.

Unfortunately, many of these peaks, although challenging and worthy climbs in their own right, often get overshadowed by the taller and more dramatic mountains of the Alps. Even today, many of the climbs first completed during this silver age remain unknown to aspiring and accomplished mountaineers, alike.

As an increasingly large number of European high peaks saw their first ascent during the silver age of alpinism, many of the foremost climbers of the era started to set their sights on mountains much higher and much loftier than those of the Alps. Leaving behind their idyllic mountain chalets of the Alps, the aristocratic climbers of the late 1800s took their hemp ropes and hobnail boots to the Caucasus, the Andes, the Rockies, and, most famously, the Himalaya.

To the roof of the world

These days, most people could tell you that Mount Everest is the tallest mountain on planet Earth. At 8,848 meters (29,029 feet) tall, Mount Everest rises out of the Khumbu region of Nepal in dramatic fashion. With 8,516 meter Lhotse on its south flank and 7,861 meter tall Nuptse to the west, the Everest massif physically commands the respect that its tallest peak deserves, yet has drawn climbers to its rolling foothills and rocky ridges ever since the mountain became known to the British in the 1800s.

Despite evidence of the region around the mountain having been inhabited since at least 800 BCE, the first records documenting Mount Everest’s record-breaking height didn’t come about until the 1715 survey conducted by the Qing Dynasty of China. Although it was known to the Chinese as Mount Qomolangma and to the people of the Khumbu region for countless generations, the tallest peak in the world was relatively unknown to foreigners until decades after the start of the British’s Great Trigonometric Survey of India in 1802.

After reaching the foothills of the Himalaya in the 1830s, the survey, which set out to fix the locations and heights of the world’s tallest peaks, finally set up in the Terai region just south of Nepal, which parallels the mountain range. Despite the then-closed borders of the Kingdom of Nepal, the torrential rains of the region, and the incessant corporeal threat of malaria, the survey finally began to make detailed observations of the world’s highest peak in 1847.

At the time, Kangchenjunga was considered to be the world’s highest peak (it’s actually the third highest), but after making several observations of the mountain, Andrew Waugh, the British Surveyor General of India, determined that another mountain - then named “peak b” - could also have claims to the title. Needless to say, this “peak b” did, indeed live up to the hype and was declared the highest mountain in the world in 1856.

Despite their claims that they wanted to preserve local names as much as possible during the survey, Waugh argued that there was no one commonly used local name for the mountain, so he decided to name the peak Everest after his predecessor, Sir George Everest. Although they may have been the first to accurately survey and document the mountain, Waugh and his team could not have predicted the infatuation and obsession with Everest that would characterize the upcoming era of mountaineering.

Early Himalayan climbing

After the completion of the Great Trigonometric Survey in the early 1870s, climbers quickly set their sights on the highest peaks in the world. Although many of the lower mountains of the Himalaya were climbed by surveyors to help them measure more distant peaks, before the completion of the survey, no one had yet travelled to the region solely for the purpose of climbing.

WW Graham, of silver age Dent du Geant fame, is credited with having made the first trip to the Himalaya solely for the purposes of mountaineering in 1883, alongside the Swiss alpine guide Josef Imboden. Although they didn’t get far in their first trek in the Kanchenjunga region before having to turn back toward Darjeeling due to Imboden’s ill health, Graham eventually went back into the mountains alongside another guide, Ulrich Kaufmann.

The duo soon set off for the Garhwal Himal and trekked around Nanda Devi, stopping short of the difficult-to-access Nanda Devi Sanctuary to turn their attention toward Dunagiri. Graham claims to have achieved a top elevation of 6,920 meters (22,700 feet) on the mountain before retreating downhill due to inclement weather. After a number of other failed attempts on other peaks, Graham and his climbing partners eventually topped out on Kabru, a 7,349 meter (24,111 ft) peak that was significantly higher than any other previously climbed mountain.

Today, these peaks are relatively unknown to all but the most dedicated of climbing history buffs, but the historical events that brought climbers to their flanks ultimately set the stage for what would become the decades-long race to the top of the world.

The Mallory era

Perhaps the best known Everest climber to never have summited the mountain (as far as we can tell, at least) is George Mallory, the English climber whose disappearance on Everest has been the stuff of climbing legend for the better part of the last century. Before he ever got to Everest, however, Mallory was just a son of a clergyman in humble Cheshire, England.

After his early childhood upbringing in Cheshire, Mallory attended boarding school in the south of England in 1896 before winning a mathematics scholarship to Winchester College. During his final year at the college, he was introduced to rock climbing and mountaineering by RLG Irving, a teacher who took a few pupils climbing in the Alps each year.

As his Winchester years drew to a close, Mallory went off to Magdalene College, Cambridge in 1905 to study history, where he soon became close with many members of the future Bloomsbury Group, including James and Lytton Strachey, John Maynard, and Rupert Brooke. Mallory’s intellectualism and interest in literature soon found him a job at a public school, Charterhouse, during which time he also met his wife, Ruth Turner.

During this time, Mallory became more and more enthralled with climbing, having taken multiple trips to the Alps with his mentor, Irving, where he climbed Mont Blanc and many other prominent peaks. When not in the Alps, however, Mallory and his friends often scaled various cliffs and crags in North Wales, particularly in Snowdonia, but were also known to frequent the Lake District, where they put up a number of rock routes that were incredibly difficult for the time. For Mallory and his peers, rock climbing was a way to train for the true climbing: mountaineering on the world’s highest peaks.

The war years brought Mallory to France, as they did for many young men of his age, but he managed to escape the war relatively physically unscathed. After the war, Mallory returned to his work at Charterhouse but was unsatisfied with the banalities of his day-to-day existence. He wanted something different, something more captivating, and something more challenging than anything he could hope to find in Europe.

Luckily enough for Mallory, that adventure did, indeed, materialize. In 1921, Mallory was invited to participate in the initial 1921 British Reconnaissance Expedition, which was organized and financed by the Mount Everest Committee to explore potential route options up Everest’s North Col. Although the Committee was initially supportive of an attempt at the summit, they eventually decided that the primary purpose of the expedition was to learn more about the mountain so a future, more knowledgeable attempt could later be made to climb the mountain - the pièce de résistance of the climbing world.

As Nepal was closed to foreigners at the time, the mountain had to be approached from the north, through Tibet, so off the group went, first by ship to Darjeeling, and then overland for the 300-mile trek to Everest. After a month of trekking, Mallory and what was left of the group that did not succumb to illness or injury, finally made it to the snout of the Rongbuk Glacier - where the walking would end and the climbing would begin.

Here at the Rongbuk Glacier, the group set up their basecamp and set to work learning to negotiate the remarkably complex terrain of a Himalayan glacier. 15 meter (50 foot) seracs were plentiful on the Rongbuk, posing a huge obstacle for the climbers, who only had experience on the much more manageable alpine glaciers of the Alps. Eventually, the group did manage to establish a Camp II at 5,300 meters (17,500 ft) and get a good look at the mountain, which would serve them well on future expeditions.

Ultimately, the expedition returned home having accomplished their goal of reconnoitring the mountain but hadn’t even come close to the summit. Luckily for Mallory, just as soon as they returned back to England’s shores, plans were already in the works for another Everest expedition, this time alongside Brigadier General Charles Bruce and distinguished soldier and mountaineer, Edward Strutt.

In 1922, just one year after his first trip to Everest, Mallory set off again for Tibet, this time with an eye towards making a serious attempt at the summit. Without bottled oxygen, Mallory led a team of climbers from the second British Mount Everest Expedition to achieve a record elevation of around 8,222 meters (26,980 ft) before having to turn around because of poor weather. A second climbing party from the group, led by George Finch, managed to reach an elevation of 8,321 meters (27,300ft) by using bottled oxygen for both climbing and sleeping.

Mallory attempted to organize yet another attempt on the summit during this second expedition, but the monsoon had arrived and heavy snows hampered their progress. While trudging through waist-deep fresh snow, an avalanche tore through Mallory’s climbing party, killing seven Sherpa along the way. Thus, the expedition turned back from the mountain and returned home.

Not long after his return home, Mallory set off on a speaking engagement tour of the United States to earn some extra money as he had left his work behind to make these attempts on Everest. It was during this time that Mallory was asked by a New York Times reporter, “Why did you want to climb Mount Everest?”, to which he famously replied, “Because it’s there.”

Unfortunately, Mallory would have to wait two whole years for yet another attempt on the mountain. The 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition was organized to finally reach the summit of the world’s highest peak. Mallory, aged 37 at the time, knew this would likely be his last shot at the summit before he would be too old to be up for the challenge.

The expedition itself was borne out of a desire to bring national prestige to Great Britain by ‘conquering the third pole’ (the world’s tallest mountain) as many Brits had previously tried, but failed to be the first to reach the North and South Poles. Despite one previous failed attempt (the 1921 expedition was mainly for reconnaissance), the Mount Everest Committee remained steadfast in their desire to see the British flag waving at the top of the world.

Mallory was, once again, chosen to be a part of the expedition as a mountaineer, along with the young Andrew “Sandy” Irvine, who was just 22 at the beginning of the expedition. Once they arrived at Darjeeling, the expedition began the arduous trek to the north side of Everest, where they set up multiple camps for their attempts on the summit.

The first summit attempt, spearheaded by Charles Bruce and Mallory, failed to make it past 8,170 meters (26,800 ft) but did manage to set up Camp V and Camp IV on the mountain. As Bruce and Mallory started off downhill, they met up with two other group members, Norton and Somervell, who were on their way up to setting a world altitude record of 8,570 meters (28,120 ft), which would not be surpassed for another 28 years. Norton became snowblind during the course of the attempt, so they eventually retreated back down the mountain.

At the same time, Mallory geared up for yet another attempt on the mountain, this time with oxygen, and this time with young Sandy Irvine. Although Irvine had no previous high altitude climbing experience, he was quite a practical person and was able to easily fix the oxygen equipment the duo would use on the climb. Thus, the two set off up the mountain on the 6th of June.

After that, all is a mystery. Although the rest of the expedition received a series of messages from Mallory and Irvine (carried down the mountain by porters), their last note to the group arrived on June 7th. By June 8th, they were making an attempt on the summit, at which point, fellow expedition member Noel Odell last peered through his camera and saw Mallory and Irvine climbing up the North East Ridge toward the summit.

They were never heard from again, and there is still much debate over whether the duo made it to the summit before meeting their end on the mountain. Although the expedition eventually returned home without Mallory and Irvine’s bodies, the debate over their potential success was renewed when another expedition organized by renowned climber, Conrad Anker, found Mallory’s body on the slopes of Everest, some seven decades after the third British Mount Everest Expedition.

The interwar years

As one might imagine, the loss of mountaineers in the prime of their climbing careers on the world’s tallest mountain was a shock to the climbing community around the world. As one might also expect, however, this did little to deter people from climbing. Rather, the still as-of-yet unclaimed first ascent of Everest was yet another spark that encouraged people around the world to start climbing to new heights.

Across the pond, in the United States, climbing and outdoors clubs sprouted up as people pulled themselves out of the depths of the great depression, looking for meaningful social interaction and ways to get outside the city. Groups, such as the Appalachian Mountain Club, the Sierra Club, and The Mountaineers pioneered the concept of combining outdoor adventure with social activity, which helped solidify outdoor pursuits as more of a mainstream activity, even though rock climbing and mountaineering were certainly still on the fringe.

These clubs filled a critical role for the interwar years generations, as the Great War had taken its toll on the mental and physical well being of people across the globe. Climbers, such as Robert Underhill, brought back the use of pitons and rappelling to Yosemite Valley after spending time climbing in Europe. These new techniques made climbing more accessible to others in these clubs, who soon started to set up small schools for teaching other members the skills they needed to get into the mountains.

That being said, the interwar years also brought about a variety of developments in climbing technology, which have been critically important as climbers sought to move away from mountaineering and alpinism as the only true forms of the sport and toward the solidification of pure rock climbing as a valuable pursuit.

Two technological developments of the interwar years stand out above the rest, however: the rubber climbing shoe and the nylon rope. Before the advent of rubber as a suitable material for use as an outsole on a shoe, climbers were stuck in leather-soled boots outfitted with steel cleats, commonly known as hobnail boots.

These boots were woefully inadequate for climbing and were blamed for many deaths in the mountains. Luckily, a young Italian shoemaker, named Vitale Bramani developed a way to create “lugs” out of rubber, founded the company now known as Vibram and revolutionizing the climbing world with a new kind of high-quality footwear.

Around the same time, chemical company DuPont was experimenting with a synthetic thermoplastic polymer that would eventually become nylon. The product quickly proliferated, finding itself a reliable spot as a material in many of our most commonly used items. As World War II broke out, DuPont and other companies worked tirelessly to find a way to replace the silk and hemp strings used in parachutes with nylon fibres. Thus, we have the first nylon cord, and eventually, the development of the nylon climbing rope, which allowed climbers to push their limits on harder and harder climbs without many of the dangers associated with the easily broken hemp rope.

With the start of the fighting in World War II, recreational climbing quickly took a backseat to other pursuits as many young men were shipped out to fight for their countries. That being said, climbing was, in fact, critical to the development of the 10th Mountain Division, the mountain warfare unit of the United States Army. The 10th Mountain Division developed out of a need to be adept at fighting in the non-traditional and alpine terrain of Europe, where it saw action in Italy during World War II.

What’s important from a climbing perspective, however, is not the bravery that the 10th Mountain Division displayed in battle, but rather, the innumerable advancements in technology and technique that came about from the unit’s very existence. Indeed, the developments of the war, both as a result of the advancements of the 10th Mountain Division were critical to the future of climbing.

Post-World War II

Back on the other side of the pond, the United Kingdom was still trying to piece itself back together the brutality of the Second World War. Not only had the war taken its toll on the people and infrastructure of the United Kingdom, the British Empire, itself was also under threat as its colonies and dependencies sought to regain their independence.

At its height, the British Empire covered over 24% of the Earth’s total land area and controlled nearly a quarter of the world’s population as a result of Britain’s dominance both at land and at sea. During this time, the sun never did set on the British Empire, whose reach expanded around the world. Throughout World War II, many of the British colonies in East and Southeast Asia were occupied by Japan and despite the overall victory of the Allied forces, the damage to British prestige had already begun and the Empire started to spiral quickly out of control.

With the loss of India - the veritable jewel of the crown in the British Empire - in 1947, Britain was seeking to regain its place as a major player on the global stage. The answer? Finally, succeed in reaching the top of the world. Thus, yet another British Mount Everest Expedition set out in 1953 to climb the infamous mountain, this time approaching from the south and with Colonel John Hunt at the helm.

In the aftermath of World War II, China annexed Tibet and closed that border to foreigners while Nepal opened itself up to the outside world for the first time. A Swiss expedition in 1952 managed to reach an elevation of 8,595 meters (28,199 ft) - a new elevation record - on the southeast ridge of Everest, having approached the mountain from Nepal.

The 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition decided to follow suit. The British Mount Everest Expedition was joined in Nepal by two Kiwis, Edmund Hillary and George Lowe, and some 350 porters and Sherpas, who had arrived in Kathmandu on March 10th to help ferry loads to the mountain. The Sirdar, or leader of the porters, was Tenzing Norgay, who would play a critical role in the events to come.

After just a few weeks of trekking from Kathmandu, the group eventually reached Thyangboche on March 26 to start their acclimatization and set up base camp. The main challenge to the route from the south side of Everest started right after leaving basecamp: the dreaded Khumbu Icefall.

Weeks of reconnoitring and setting up advanced camps up the mountain took their toll on the group and resulted in one failed summit attempt in mid-May. But, having been well rested at basecamp during the first summit attempt, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay set off on May 27th for one last shot at the top.

After two days of climbing, the duo did, indeed, make it to the top of the mountain, reaching the roof of the world at 11:30 am on May 29th as a climbing team. They descended with minimal issue and returned to basecamp as heroes and veritable legends. News travelled slowly in those days, so it took time for the folks back home in the UK to learn about this stunning achievement. Coincidentally, the news arrived in London on June 2nd, the morning of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation.

Whether you want to look at this coincidence as just happenstance or as the dawn of a new age in the world is a matter of personal preference. That being said, the first ascent of Mount Everest had a huge impact on the international climbing community as more and more people started taking to the mountains and experiencing the freedom of the hills.

Yosemite Rising

Back on the other side of the globe, in Yosemite National Park, a group of climbers were making a name for themselves and their sport amongst the stunning glacier-carved granite walls of the Valley. Although people have been living in the Valley for countless generations and scrambling the peaks of the Sierra for nearly two centuries and people did climb in the Valley in the interwar years, it wasn’t until the 1950s that Yosemite really found its place as the global epicentre of big wall climbing.

In the 1950s, two of the greatest climbing prizes of Yosemite - Half Dome and El Capitan, were still unclimbed. Despite the efforts of dozens of dozens of climbers, no one had yet been able to ascend their sheer faces. Such prizes breed competition, which is exactly what Warren Harding (not the future president) and Royal Robbins found themselves entrenched in during the late 1950s.

In 1957, Harding charged his Corvette into Yosemite Valley to beat Robbins to the top of Half Dome, only to find that Robbins was already well on his way up the Northwest face. Robbins managed to make the ascent of the Northwest face in just five days with the help of Jerry Gallwass, setting the stage for the future of big wall climbing.

As Half Dome had already been taken, Harding quickly set his sights on El Capitan. Over the course of a year and a half with 47 days spent on the rock, Harding, George Whitmore, and Wayne Merry finally made it to the top of El Capitan in November 1958 after a final 12-day push. Harding, with his wine drinking, counter-culture antics, soon became a hero, which only further irritated Robbins into repeating the ascent in a better fashion. In the 1960s, Robbins made a quick and efficient second ascent of the Nose route on El Cap and then made a first ascent of the 35 pitch Salathe Wall in 1961, alongside Yosemite Greats Tom Frost and Chuck Pratt.

These new routes inspired a generation of counterculture Beatnik climbers to take to the Valley, squatting illegally in the famous Camp 4 for months on end. Climbing became not just an activity for these people, but a way of life. Climbing greats, such as Robbins, Frost, Pratt, Yvon Chouinard, John Long, and Jim Bridwell set the standard for climbing in the 60s, but little did they know what would happen from there.

The dawn of a new age

The 1970s in the Valley and around the world saw a huge increase in the number of climbers. Moreover, there was a monumental shift in climbing ethics during this time, with an increased emphasis on clean, free climbing, as opposed to hammering in pitons as one aid climbs up a route. Free climbing standards rose drastically, as the Yosemite Decimal grading system became open-ended and climbers pushed the limits of what was possible.

Climbers made first ascents of incredibly difficult and sustained routes, such as John Long, John Bachar, and Ron Kauk’s first ascent of Astroman, but also tried to take older routes to the next level by climbing The Nose in a day. In the 1980s, free ascents of aid routes became the norm, as Todd Skinner and Paul Piana made a team free ascent of the Salathe Wall and Ray Jardine brought spring-loaded camming devices (SLCDs - aka cams) to the forefront of climbing as he made ascents of routes otherwise thought to be impossible.

Sport climbing and bouldering rose in popularity, too, as climbers looked for ways to stay strong and develop even when a big wall climb was out of the question. That being said, in the Valley, the emphasis was still on pushing the limits on big routes. Lynn Hill made history in the early 1990s, becoming the first person to make a true free climb of El Cap and then repeating the effort a few years later by free climbing the granite monolith in a single day.

Since then, the limits have been pushed and pushed well past what we ever thought was possible. Climbers such as Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgenson have set a new standard for sustained and difficult climbing, with their first ascent of The Dawn Wall on El Cap. Meanwhile, Alex Honnold has shocked the world by being, well, Alex Honnold, and free soloing routes that take most of us mere mortals a week to complete - doing it all in less than a day and with nothing but a chalk bag between him and the Valley floor.

Rock climbing and mountaineering have certainly come a long way since their humble beginnings in the jagged peaks of the Alps and the craggy hills of North Wales. Although the equipment has improved and the routes have become more difficult, climbers still take to the hills for the same reasons: the pure joy of adventure and the quest to find oneself among immeasurable beauty. The boundaries of climbing have been tested and the limits have been smashed. Clearly, there’s only one way to go from here, and that’s onwards and upwards towards the future of climbing.